What Causes Idiopathic Scoliosis?

Exploring the Factors Behind the Curve

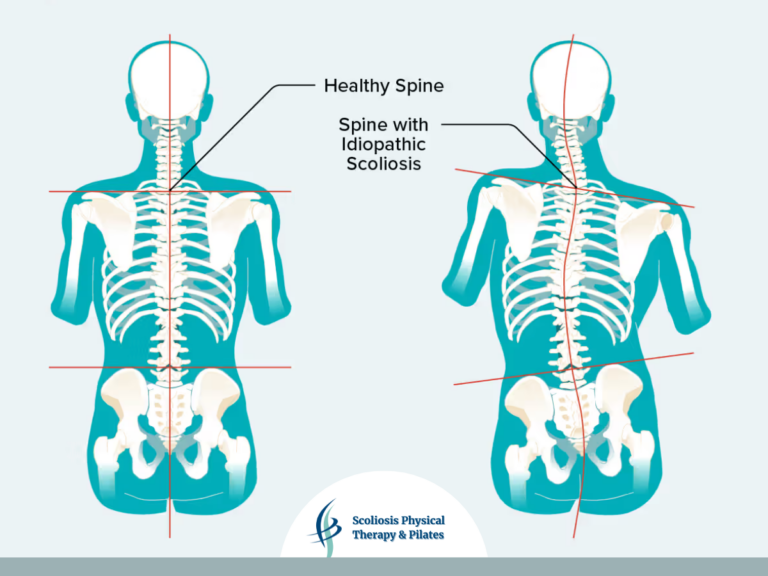

Idiopathic scoliosis (IS) is a condition where the spine curves in three dimensions, mostly during the teenage growth spurt. What makes IS so challenging to understand is that its exact causes remain unknown despite decades of research. It’s not caused by one single issue but a mix of factors, including genetics, hormones, biomechanics, and the nervous system. Studies by experts like Lowe, Yarmon, and Robins have uncovered important clues, but much more research is needed to fully solve the puzzle and create better treatments.

Why Scoliosis is So Complex

Scoliosis isn’t caused by one thing—it’s a mix of issues working together. Experts have found that:

- Genetics can make some people more likely to develop scoliosis.

- Connective tissue problems may weaken the spine’s support.

- Hormonal changes during adolescence can make curves worse.

- Biomechanical factors, like uneven growth, can add extra stress to the spine.

Even with these discoveries, we still don’t know the full picture. That’s why more research is needed to better understand this condition.

How Genetics Play a Role

Research shows scoliosis often runs in families, but it’s not caused by just one gene. Instead, multiple genes work together to increase the risk. Some key genes linked to scoliosis are:

- LBX1: A gene involved in spine development.

- GPR126: Affects bone growth and connective tissue.

- CHD7: Plays a role in tissue and nerve development.

- MMP3/MMP9: Help remodel connective tissues in the spine.

While these genes offer important clues, scientists are still figuring out how they contribute to scoliosis.

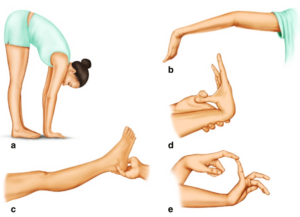

Connective Tissue and Joint Laxity

Connective tissue, which helps keep the spine stable, may be weaker in people with scoliosis. Research by Yarmon and Robins found that:

- Many scoliosis patients have looser joints (joint laxity) in the spine and ribcage, making it harder for their spines to resist curving.

- They also tend to have weaker muscle tone, which adds to instability.

The Beighton score, a simple test for hypermobility, is often used to measure joint laxity. People with higher Beighton scores are more likely to have hypermobility, which can contribute to instability in the spine and other joints.

These findings highlight the importance of strengthening muscles and supporting connective tissue in scoliosis treatment.

Hormones, Melatonin, and Vitamin D

Hormonal changes during growth spurts can make scoliosis worse. For example:

- Growth hormones and estrogen can speed up uneven spinal growth.

- Some scoliosis patients have low melatonin levels or don’t respond well to melatonin. Since melatonin helps with balance and muscle control, these imbalances might play a role.

- Vitamin D levels may also influence scoliosis. Vitamin D is essential for bone health and muscle function, and deficiencies have been linked to weaker spinal support and increased risk of scoliosis progression.

More studies are needed to fully understand how hormones, melatonin, and vitamin D interact and contribute to scoliosis.

How Biomechanics Contribute

Mechanical forces affect scoliosis:

- Rapid growth during adolescence can put uneven pressure on the spine.

- The “vicious cycle” of scoliosis, described by Stokes, shows how even a small curve can snowball into a bigger issue.

- As the spine curves, uneven forces are created that put extra stress on certain areas.

- This stress and added pressure on specific areas of the spine causes the curve to worsen.

- Over time, this self-reinforcing loop can make scoliosis more severe if left unchecked.

Breaking this cycle involves improving spinal stability, correcting muscle imbalances, and addressing any postural issues early on to prevent progression.

What Does This Mean for Treatment?

- Personalized Plans:

- Treatments should look at the entire individual, not just their curve.

- Targeted Therapies:

- Strengthening connective tissue and muscles might help stabilize the spine.

- Research on hormones and melatonin could lead to new therapies.

- Physical Therapy:

- Exercises like the Schroth Method focus on axial elongation and derotation of the scoliosis curve to prevent collapse and worsening of the curve.

- Pilates

- Pilates is a great way to strengthen muscles and improve posture to manage scoliosis.

The Future of Scoliosis Research

We’ve made progress, but there’s still so much to learn. Future research should:

- Dig deeper into how genetics, hormones, and biomechanics interact.

- Develop better ways to detect scoliosis early.

- Create treatments that address the root causes, not just the symptoms.

With continued research, we can offer better outcomes for people with scoliosis.

Conclusion

Scoliosis is a complicated condition influenced by genetics, hormones, and how the body grows and moves. Thanks to research from experts like Lowe, Yarmon, and Robins, we’re uncovering the pieces of the puzzle. But there’s still a lot we don’t know. With more studies, we can find better ways to predict, treat, and maybe even prevent scoliosis in the future.

References

- Lowe, T., et al. (2000). “Etiology of idiopathic scoliosis: Current trends in research.” Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

- Yarmon, B., & Robins, P. (2005). “Joint laxity and muscle tone in idiopathic scoliosis patients.” Spinal Research Review.

- Cheng, J. C., et al. (2007). “Genetic mapping of idiopathic scoliosis.” Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research.

- Grivas, T. B., et al. (2006). “Melatonin’s role in the pathogenesis of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.” Scoliosis Journal.

- Schlenzka, D., et al. (1996). “Neurological and biomechanical aspects of idiopathic scoliosis progression.” European Spine Journal.